Badgers

The Eurasian badger (Meles meles) has been present in Great Britain for thousands of years. Since the demise of the wolf and the bear in the UK, man and his actions remain the badger’s biggest threat.

In the 1800s badgers were thought to be practically extinct in Westmorland, Cumberland, Northumberland and Durham. In the 1900s they started to recover as gamekeeper pressure reduced partly due to two world wars.

The behaviour described in this website is relevant to the UK – for instance where it is common for badgers to play, groom and socialise on emergence from their setts, badgers in Poland (where there are still wolves and bears), reportedly shoot out of their setts like bullets!

Habits

Badgers belong to the weasel family (Mustelidae) all of which are carnivorous and have a musk gland underneath the tail. The Badger slightly bucks this classification by being omnivorous, which is borne out by their diet and the configuration of their teeth.

Badgers are fossorial (they dig) and live in setts which is a series of tunnels and chambers engineered by the badger and extended as necessary. Up to an area 35m x 15m and 4m deep.

Badgers live in social groups (clans), in a hierarchy and are territorial. The size of the group and territory depends on the size and quality of the foraging area, the availability of suitable ground to dig into for sett building and the vicinity of other clans.

A clan could comprise between 3 and 20 badgers, with an average of about 6. As an average, there might be 10 adults per square kilometre given good habitat. A badger may live up to 10 years, usually about 7 years. A good percentage of cubs do not make it to their first birthday.

The territory could be anything from 30 acres to about 175 acres, or even greater (400-700 acres) in the north of Scotland where foraging can be in poor marginal areas. Badgers can be found on suitable ground up to a height of about 500m and they are almost absent from areas such as fenlands.

Badgers are nocturnal, but in quiet places will emerge in the early evening during the Summer. They do not hibernate during the Winter. They do however, build up fat stores in the Autumn as their activity is curtailed during the Winter, especially in December/January and during spells of severe weather. They can probably manage without food for up to 5 days. As they are adapted to living underground they have a low metabolic rate and during the Winter, their body temperature is low.

Badgers by Numbers

- Estimated population between 250,000 – 310,000 in the UK.

- Around 50,000 are killed on the road.

- Estimated 10,000 are killed by baiting/sett digging etc.

Around 70,000 badgers have been killed since 2013 as a result of the governments Bovine TB prevention measures. We oppose the continuing and expanding widespread cull of badgers. Good cattle husbandry, control of movement between marts/farms and testing are the key to controlling the disease which got out of control with unchecked restocking following the Foot & Mouth outbreak in 2001. It costs £339 to kill a badger by one of the culling businesses which sprung up around government policy. Bovine TB is complicated. There is more than one strain of bTB in circulation which can be tracked back to its source – for instance the outbreaks in cattle (and subsequently badgers) in the Shap/Penrith areas was tracked back to cattle brought in from Northern Ireland. We believe farmers in our area are more informed and are careful when bringing cattle into the area which is why there are relatively few outbreaks - however we have to be ever watchful.

Physical Characteristics

The badger is physically strong and even though its legs are short, can run quite quickly and is capable of climbing fences if motivated.

Size averages: 686-803mm, 9.1–16.7kg (males), 673-787mm, 6.5–13.9kg (female)

Their feet are padded with five toes and claws. The front pair are larger and used for digging and defence.

Badgers have a strong bite and they bite each other on the rump during serious disagreements. Sometimes these wounds will kill them.

The badger’s striped face could have evolved as a warning flash to predators.

Its hair is coarse comprising guard hairs (90-100mm long) and during the winter they have an under-fur. The strands are flat sided, appearing black and grey, occasionally ginger/brown or rarely, albino.

Senses

Badgers have an excellent sense of smell and their long rubbery snout can be curled back when foraging on the ground to hunt for worms. They are also able to block their nostrils.

Their sight is not too good and are usually spooked by an unusual silhouette or movement. They probably see in shades of white, black and grey.

They have whiskers on the snout and above their small eyes which helps them feel their way in confined spaces.

Hearing is quite good and their ears are small, set on the side of the head.

Glands in the anus, between the tail and the anus, and between their toes are used for scent-marking paths, their setts, territories and each other.

Diet

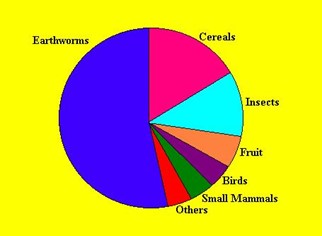

Their diet is omnivorous and worms predominate, so short grass/pasture is important. Other food will include insects, wasp nests, larvae, berries/fruit fall, bulbs, young rabbits, some cereal crops etc. Periods of drought are difficult when worms are driven deep underground, and that might be a time when they venture into gardens and cross more roads, leading to more casualties. They may also move temporarily to an outlier sett closer to the source of a seasonal crop of berries, apples or cereal.

Their teeth reflect their varied diet, having incisors and canines for cutting and premolars and molars for grinding.

Latrines

For a lot of us interested in badgers, the discovery of a fresh deposit of dung can be quite exciting because it is evidence the badger is active in the area, even if you do not know or have not got access to the sett. A dark brown dollop (which might include berries or cereal) is deposited into a small hole dug for the purpose. They smell "earthy". Latrines are also used to mark territory boundaries, which in urban areas might just be around the immediate sett area. We record latrine locations on the database where the location of a sett is unknown - this can be useful intelligence when looking at planning applications/proposals.

Home sweet home – The Sett

A badger sett is a work of engineering! Setts are found in woods, embankments, rock strata, mining spoil, even drainage pipes and relatively flat fields. The preference would be a sett dug into a slope with trees above to act as protection. They can exist in the same spot, despite interference, for decades - centuries even. Although severe damage may cause them to move to another part of their territory.

A territory will have a main sett which is usually where the cubs are born, one or more subsidiary or outlier setts and other odd holes. Some of these are connected by very clear paths.

There might be only 1 or 2 entrances, or up to 10-15 but they will not necessarily all be in use at any one time.

A sett area can cover an area 35m x 15m, up to 4m deep.

Badgers are clean animals and bedding is regularly turned out, aired and replaced. The spoil heaps can be huge, or there could be none. An entrance is generally about the same size as a piece of A4 landscape paper but can be bigger, with one or two tunnels leading from one entrance. The badger has its very own flea, which might be another reason badgers temporarily move setts to give it an airing.

A fox may also use part of a sett – but this usually becomes impossible when they both have cubs.

Procreation

A badger clan comprises males and females of varying ages. Males reach sexual maturity at about 24 months and females around 12-15 months. Although there will often be an alpha boar, all mature males will try their chances to mate given the opportunity. It may suit a sow to have all the boars thinking the cubs are theirs! Boars from neighbouring territories will also chance their luck despite the risk of attack by the resident clan. More than one sow in a clan may give birth and the cubs are looked after in a nursery so that the sows can forage to keep up their condition - either by other mothers or other females.

Some mature badgers will leave their birth sett to create territories of their own or take over a neighbouring vacancy.

Mating takes place at any time of the year but mostly between February and April. Any fertilised eggs (blastocysts) are held in suspended animation until December when the fertilised eggs implant into the wall of the uterus and start to develop. The cubs are born eight weeks later (around mid-February). Because of delayed implantation and multiple opportune matings, it is perfectly possible that the cubs born have different fathers.

Usually 2 or 3 pink/grey cubs are born. They are about 12cm long and with closed eyes. They are suckled underground for up to 8 weeks and are weaned at around 12 weeks, after which they will get their adult teeth. They will be closely supervised by the group when they first appear above ground for a few weeks during the Spring. The cubs will hopefully weigh about 10kg by the Winter but it is thought about 60% do not make it through their first winter.

Dry Springs are a problem when worms are not available and there are no berries or much in the way of crops because this leads to badgers foraging further afield to sustain themselves and their cubs. This can be when the bulk of the road traffic deaths occur.

A Year in the Life of a Badger

January Activity quite low especially in heavy frosts.

February Cubs are born. Mating begins. Territories are marked.

March Clearing out and collection of bedding becomes obvious on spoil heaps.

April Cubs emerge from sett, under supervision.

May Mating continues. Cubs gain more freedom.

June Emergence early evening in quiet places. Cubs forage with adults.

July Foraging. A sett maybe vacated temporarily if invested with fleas.

August Foraging might include cereal crops/fruit.

September Mating continues. Lots of housekeeping.

October Diet includes berries and nuts. Increase in weight ready for winter.

November Food harder to find.

December Blastocysts implanted in uterus.